TL;DR: Your most expensive employees are acting as human middleware. Discover the hidden “Shadow Payroll” draining your budget—and why adding more integration tools is only making the problem worse.

The monthly business review is a corporate theatre of the absurd.

It usually happens on the third Tuesday. The VP of Sales presents a pipeline value of $4.2 million. The Head of Finance interrupts, pointing out that billed revenue is only $3.1 million. The Head of Customer Success looks confused, noting that according to their dashboard, active contract value is $3.8 million.

The meeting descends into an archaeological dig. Who pulled the data? When? Did the export include the pending renewals in Salesforce, or just the signed contracts in Xero?

For the next hour, your most expensive executives are not discussing strategy. They are debugging the definition of the word “customer.”

This ritual is the visible tip of an invisible crisis. Beneath the surface of modern operations lies a “shadow payroll”: the vast, unmeasured sum of money businesses spend paying smart people to act as human middleware.

Fragmentation by Design

The genesis of this crisis was innocent enough. In the quest for efficiency, the modern enterprise unbundled itself. Sales bought the best CRM; Engineering bought the best issue tracker; Finance bought the best ledger.

The result is a paradox: businesses have never possessed better tools, yet operational friction has never been higher.

According to Okta’s latest data, the average mid-market firm deploys 137 distinct applications. Each is a cathedral of logic, optimized for a specific priesthood. But cathedrals do not talk to one another.This has birthed a new economic reality. Operations teams no longer manage operations; they manage the empty space between tools. They are the “Alt-Tab” generation, toggling between browser windows 1,200 times a day—a figure cited by Harvard Business Review—to manually ferry context from one digital island to another.

Gallup estimates this context switching costs the U.S. economy $450 billion annually. But for the individual operator, the cost is more visceral. It feels like swimming through glue.

When the System Snaps

Most leaders do not realize they have an architectural problem until they hit one of three specific breaking points. These are the triggers that bring people here:

1. The “Where Is It?” Panic

A client calls with a frantic request. To answer it, your account manager needs the contract (in Google Drive), the project status (in Asana), and the billing history (in QuickBooks).

The delay isn’t caused by a lack of competence; it is caused by the archaeology required to reassemble a single client’s reality from three different shards. When “knowing the customer” requires opening five tabs, you do not actually know the customer.

2. The New Hire’s Glaze

Watch a manager onboard a new employee. Listen to the apology that inevitably comes halfway through: “I know this seems weird, but we have to create the project in Tool A, then copy the ID number into Tool B, and don’t forget to tag Finance in Tool C or they won’t send the invoice.”

That apology is the sound of broken architecture. It is the admission that the process serves the tools, rather than the tools serving the process.

3. The Reporting Lag

The CEO asks a simple question: “How profitable was the Q4 marketing campaign?”

In a unified system, this is a query. In a fragmented one, it is a project. It requires an analyst to export ad spend, export CRM data, export billable hours, clean the CSVs, map the fields using VLOOKUP, and pray the data hasn’t changed in the interim. The answer arrives three days later—too late to be useful.

Bridging the Unbridgeable

The conventional cure for this malaise is “integration.” If the silos can’t speak, the logic goes, we will build bridges.

Companies hire engineers to write scripts connecting HubSpot to Jira. They purchase middleware platforms like Zapier or MuleSoft. They celebrate when the data flows.

But this solution is a mirage. Integration automates the movement of data, but it does not solve the fundamental problem: Schema Dissonance.

Consider the humble “Project.”

- To the PM Tool, a Project is a collection of tasks and deadlines.

- To the CRM, a Project is a deal stage with a dollar value.

- To the Finance System, a Project is a billing code and a ledger of expenses.

Connecting these systems via API is like hiring a translator to run between three people shouting in French, German, and Japanese. You may achieve basic communication, but nuance is lost, and the latency is excruciating. Gartner finds that companies spend up to 40% of their engineering talent just maintaining these fragile bridges. When one system updates its API, the bridge collapses, and the shadow payroll expands.

Unifying the Atom

There is a quieter, more radical school of thought emerging: Architectural Unification.

This approach argues that the “best-of-breed” era was a mistake. It posits that the friction of fragmentation outweighs the benefit of specialized features.

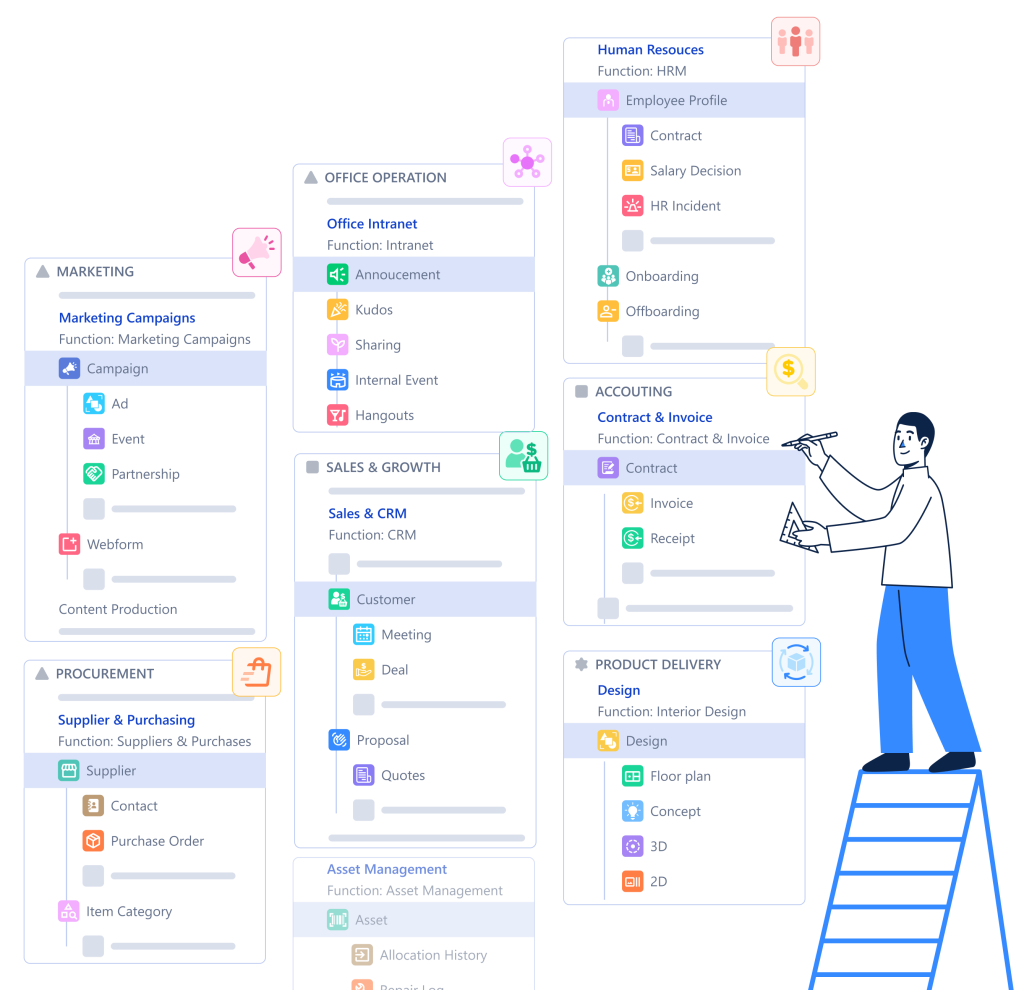

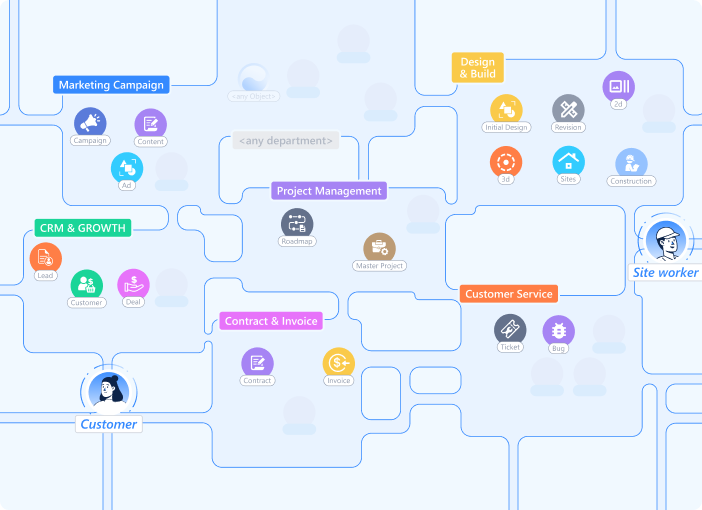

The solution is not to connect disparate databases, but to build on a single, flexible foundation—what we call a Universal Object architecture.

In this model, a “Customer” is not three different records synchronized by scripts. It is a single object. Sales views it through a pipeline interface; Support views it through a ticket interface; Finance views it through a billing interface. But they are all looking at the same atom of data.

When Blue Media, a rapidly scaling agency, adopted this unified approach, the “Wednesday Morning Ritual” of data reconciliation vanished. They didn’t train their team to copy-paste faster; they removed the need to copy-paste entirely.

Auditing the Invisible

The $450 billion figure is abstract. Your organization’s share of it is not. To calculate the tax you are paying for fragmentation, apply this simple heuristic:

- The Sync Tax: Estimate the hours per week your team spends exporting, importing, or reconciling data.

- The Search Tax: Estimate the time spent looking for information that “should be right here.”

- The Latency Tax: What is the cost of a decision made on Wednesday using Monday’s data?

For most mid-market companies, the sum of these taxes roughly equals the cost of their entire IT budget. You are paying for your software twice: once in license fees, and again in the labor required to compensate for its design.

The modern operator is tired of being a data janitor. They were hired to think, to build, and to sell. The organizations that win the next decade will be the ones that liberate their talent from the tyranny of the Alt-Tab.